|

|||

|

|

|

|

Guest Columns

Perspective:

WCMA

The whey problem and California’s solution

John Umhoefer

John Umhoefer is executive director of the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association. He contributes this column monthly for Cheese Market News®.

In April, USDA asked small businesses to submit concerns about federal milk marketing orders. It was interesting timing in light of the new proposal from dairymen to bring California into the federal order system.

Today, California, operating outside of federal orders, has a better solution to milk pricing when it comes to one key factor: the value of whey.

Dairy producers gain a value for whey in their milk price in California and in states regulated by federal milk marketing orders. But California has a better solution for valuing whey and while the explanation is a bit technical, the fundamental reason why California is on the right track isn’t technical at all.

The reason is this: Cheesemakers pay dairy producers the value of dried whey. But most cheesemakers don’t produce dried whey. When whey prices are high, many cheesemakers take immense losses.

USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) surveys cheese and whey plant operations for their production data, and includes plant statistics in their annual summary. Nationally, there are only 32 dried whey plants, equal to only 6 percent of the 529 cheese plants included in the NASS survey. Wisconsin has 126 cheese facilities and 10 dried whey plants or 12.6 cheese plants for every dry whey facility.

The ratios aren’t much better when comparing dried whey production to estimated available whey solids. U.S. dried whey production volume is equal to only 14.1 percent of estimated whey solids and Wisconsin dried whey production uses only 17.8 percent of total whey solids in the state. Despite the very low utilization rate of whey solids for dried whey, this product remains the sole determinant of the other solids price in the Class III milk price paid to dairy producers.

Cheese manufacturing sites in Wisconsin buy milk from dairy farms and pay these patrons the value of dried whey in the Class III milk price. But these cheese manufacturers do not earn the value of dried whey from the marketplace. The majority of these Wisconsin cheese plants produce skimmed, wet whey, which is a lower value commodity than dried whey.

It’s a fundamental flaw in federal milk marketing order milk pricing – a built-in discrimination against small and mid-sized cheese manufacturing businesses that cannot begin to afford the cost of dried whey manufacturing. Production of dried whey requires massive capital investment, in the tens of millions of dollars, and this investment is not possible for most cheese manufacturing small businesses.

California recognized this threat to small and mid-sized cheese producers and has a simple solution in its state milk marketing order. The value of whey is capped at 75 cents per hundredweight of milk. When the dried whey price reaches 60 cents per pound or higher, the value paid to producer halts at 75 cents in the milk price. But in the federal order system there’s no cap on the value of whey paid to dairy farms — as dried whey prices move higher and higher, the Class III milk price rises and cheesemakers bleed red ink.

Interestingly, it’s not only small and mid-sized cheese plants with wet whey to sell that face trouble. Even larger cheese plants that have spent millions on ultrafiltration to produce value-added whey protein concentrate are getting burned by the dried whey value in federal order milk pricing. Why?

Because for the last 39 months, the value of 34-percent whey protein concentrate (WPC) has been lower than dried whey (pound for pound of protein).

Whey protein concentrate in various concentrations has become the preferred product in the marketplace. Concentrating protein creates a lactose-rich permeate that also has a value in the marketplace. As these products have increased in volume, output of dried whey has decreased, and dried whey has become the higher value product in the marketplace. Like their fellow cheesemakers selling only skimmed, wet whey, these more sophisticated whey protein manufacturers do not earn the full value of dried whey in the marketplace, despite millions of dollars in investment.

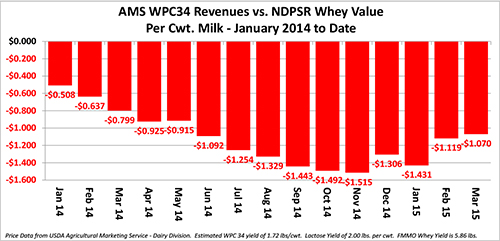

The situation has worsened over the past year. Revenues from 34 percent WPC were 50 cents below dried whey in January 2014, but fell to more than $1.50 lower than dried whey by November and have been more than $1.00 below dried whey since last June (see chart accompanying this column).

When USDA sought comments on federal orders in April, it asked for changes to “minimize any significant economic impact of rules upon a substantial number of small entities.” California, currently outside the federal order system, has one excellent solution to reduce the economic impact of these rules: cap the value of whey in milk prices and stop forcing cheesemakers to overpay for a product they do not make.

CMN

The views expressed by CMN’s guest columnists are their own opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of Cheese Market News®.

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090