|

|||

|

|

|

|

State of the Industry

Sustainability, innovation are key to Minnesota dairy growth

Editor’s note: As part of our “State of the Industry” series we take a look at the cheese and dairy industry across the United States. Each month we examine a different state or region, looking at key facts and evaluating areas of growth, challenges and recent innovations. This month we are pleased to introduce our latest state — Minnesota.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — Minnesota, home of quality farmland, abundant feedstuffs and more than 10,000 freshwater lakes, holds several advantages for producers, processors and innovators in the dairy industry.

“This really is the place where cows should be milked. If you’re looking for a long-term, sustainable dairy industry, it makes sense to have access to high-quality feedstuff and high-quality water,” says Bob Lefebvre, executive director, Minnesota Milk Producers Association.

“Our competitive advantage is mother nature. Our land and our water. Also our people,” Lefebvre adds.

But members of the Minnesota dairy industry also admit there are some unique challenges in this state where people are vocal and passionate about protecting their natural resources.

“I think Minnesota is one of the hardest states in the Midwest to do a project in because of the public influence. No one wants it in their neighborhood,” says Mitch Davis, general manager, Davis Family Dairies, and vice president of research and development, Davisco Foods International Inc., Le Sueur, Minn. “I think Minnesota has wrestled with these controversies more than most states.”

However, dairy producers appreciate these natural resources as much as any of the state’s citizens and have worked to contribute to a sustainable model for the industry and environment.

Minnesota traditionally has had strict environmental regulations that 10 years ago were ramped up even more, Lefebvre says. And while initially regulations such as those requiring zero discharge from feed lots seemed insurmountable, dairy farmers and citizens have come together to meet these high standards.

“I think it’s friendly, but the bottom line is if you want to milk cows in our state, you have to protect the environment,” Lefebvre says. “We certainly welcome you, but you will be held to the existing high standard.”

The dairies that meet these standards are a valuable resource in Minnesota, where the dairy industry is a more than $2.5 billion segment of the economy, according to the University of Minnesota Extension. Dairy accounts for the largest segment — more than 15 percent — of agriculture production in Minnesota.

The vast majority of dairy producers in the state also raise their own feed, growing corn and alfalfa, Lefebvre says, adding that alfalfa helps to significantly reduce soil erosion and maintain the environment.

“We’re a huge economic engine to the state,” he says. “We’re good economically, and we’re good environmentally.”

• Growth and innovation

Minnesota has 87 counties and the dairy belt runs through about half of these. Dairies are most prevalent in the central part of the state in Stearns County and around St. Cloud, Minn. There also is a strong presence in the southeastern part of the state around Rochester, Minn., and the southwestern part near the South Dakota/Iowa border.

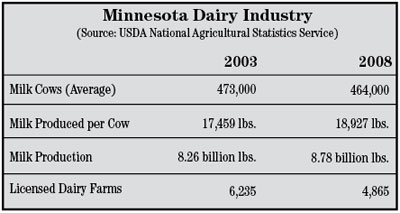

Dairy production in Minnesota hit its peak in 1964, when it had 1.3 million cows producing 11.16 billion pounds of milk, according to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Aside from a brief surge in the early 1980s and now in this decade, the state’s dairy industry generally has declined for the past 40 years.

Over the past several years, though, production and cow numbers again have started to rise. Production rose almost 700 million pounds from 8.10 billion in 2004 to 8.78 billion pounds in 2008. Cow numbers also reached a five-year high at 646,000 head in 2008.

With an average dairy herd size of 100 cows, Minnesota is home to many small family farms. And while not as much expansion has taken place over the past year due to industry-wide financial hardships, many of these farms have worked to expand and innovate over the past 5-10 years.

“Nutrition and genetics have improved every year,” says Tim Dolan, University of Minnesota extension educator, Sibley County. “In the past 10 years we have had a lot of expansion of dairy farm size, but the overall industry, at least for the short term, is more in hunker-down mode, trying to survive.”

Lefebvre says much of the recent growth is due to reinvestment and modernization on farms. In 2006-2007, he says, 28 counties in Minnesota increased in cow numbers and 41 counties increased in milk production.

“It’s been happening for the large part because farmers are reinvesting in their operations to make life easier for the cows, better managing the care for cows,” Lefebvre says. “A lot of reinvestment has taken place in the past 5-10 years.”

One dairy that recently opened in Nicollet County has invested not only in technology for its own success, but also in a partnership to help educate veterinarians and add to the infrastructure and knowledge of the industry.

The recently-opened New Sweden Dairy, which milks 3,000 cows daily and serves as a birthing center for more than 6,000 calves per year, is a partnership between Davis Family Dairies and the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine. Davisco Foods International is among the six founding donors of the new facility, and the approximately 370,000 pounds of milk produced each day at the dairy goes to Davisco’s cheese plant in Le Sueur, Minn.

Davis says the partnership began when Davis Family Dairies began plans to build a new dairy and the University of Minnesota approached them to propose including an academic portion of the dairy. The university helped to design and integrate the academic interface they wanted to include. The dairy features dormitory facilities, classrooms and teaching laboratories. The College of Veterinary Medicine will offer a hands-on rotation at the dairy for students, and Pfizer Animal Health, another founding donor, is sponsoring short courses for continuing education at the facility. The dairy already has had two or three rotations of students since July, Davis says.

As a milk processor as well as producer, Davis says it helps to increase the level of knowledge in the industry through this partnership.

“We want to do everything we can as a milk processor to expose and educate people in whatever it takes to be successful,” he says. “We want a lot of milk production in Minnesota and to do everything we can to provide resources that go beyond a single business and help other businesses.”

Davis adds that the dairy benefits by learning from the academic side, and more indirectly, more capable veterinarians will help the overall management of facilities.

“People are the biggest thing in any business to master,” Davis says. “If you can have qualified people who are able to do these tasks, it’s go to be a good thing.”

• Processing opportunities

Innovation by processors also has contributed to a successful dairy industry, Lefebvre says. In Minnesota, 15 percent of the milk produced goes to fluid production while 85 percent goes toward other manufactured products.

“It’s easy to take milk, pasteurize it, put it in a bottle and put it on store shelves. It takes innovation, creativity and smart management to make that other 85 percent work,” Lefebvre says.

Davisco Foods plans in November to complete an expansion of its Le Sueur plant that will include a new intake bay, laboratory, office building and cheese store. Associated Milk Producers Inc. (AMPI) recently switched the nonfat dry milk dryer at its Paynesville, Minn., plant to a high-value whey protein concentrate dryer in a $4 million conversion.

In addition to well-known cooperatives like Land O’Lakes and AMPI, Lefebvre says there are other players in Minnesota’s dairy industry that people don’t talk about as much, such as First District Association in Litchfield, Minn., and Bongards’ Creameries, with plants in Bongards and Perham, Minn., that also are influential and growing.

“First District Association has the largest cheese plant in the state. It’s their only plant, but they’re growing and they’re set for more growth,” Lefebvre says. He adds that Bongards’ Creameries has been improving as well, adding value to its farmers’ milk.

Artisan cheese and dairy companies also have carved out a growing presence over the last decade, offering unique and specialty contributions from Minnesota.

PastureLand Dairy Cooperative, Goodhue, Minn., started in 2000 and offers organic cultured butter and artisanal cheeses made from the milk of grass-fed cows in southeastern Minnesota. Faribault Dairy, another southeastern Minnesota company, makes Blue cheese from milk from seven area farms. It ages its cheese in St. Peter sandstone caves that are unique to this part of the country and maintain a temperature of 53 degrees Fahrenheit and humidity of 95 percent or more year round.

Faribault Dairy has averaged about 18 percent growth per year since it started in 2001. In addition to its Blue, it recently started aging a few cheeses in its caves made by other companies. This year it completed renovations of its caves and opened a small retail store in downtown Faribault, Minn., to showcase its cheeses as well as other artisan cheeses from Minnesota and across the country.

Jeff Jirik, cheesemaker and president, Faribault Dairy, says interest in artisan cheese absolutely has grown in Minnesota.

“We’re seeing a really solid interest in local and sustainable and green,” Jirik says. “We’ve had great response to the cheeses we’ve introduced in the last several years and great support from the retailing community as well.”

Despite the public support of local cheeses, Jirik says he believes more could be done by the state to help promote Minnesota dairy products.

“There’s an ambivalence you see here toward agriculture that isn’t found in Vermont and Wisconsin,” Jirik says. “They understand the resources they have there and how to research and promote it. We don’t have any promotion board for Minnesota dairy products.”

• A sustainable industry

Others also see room for improvement when it comes to state support. The Minnesota commissioner of agriculture does host a dairy advisory committee that meets regularly, and in the midst of the dairy crisis the state established a farmer assistance network and hot line producers can call for help. However, no emergency funds have been allocated for producers.

“I think the idea is noble, and I don’t want to be critical, but it the state wants to have an impact, it can and should do much more,” Lefebvre says of the assistance network and current programs.

Davis says Minnesota’s dairy industry has its challenges, such as public-driven regulatory issues, workman’s compensation laws, insurance and high taxes. However, he also believes dairies can work with the government and public to continue to benefit everyone.

“I think the future’s optimistic if Minnesota can keep its regulatory and environmental ducks in a row and keep the public educated,” Davis says.

Lefebvre says despite the current challenges, he believes Minnesota has the necessary foundation to continue growing in the future.

“I don’t want to gloss over what we’ve been through the last year. It’s been tough. But for the long-term, Minnesota is well-positioned,” Lefebvre says. “We have the natural assets that make it a good place to dairy long-term. We have great people, processors and infrastructure.”

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090