|

|||

|

|

|

|

State of the Industry

Idaho dairy industry emerging as major part of state identity

Editor’s note: As part of our “State of the Industry” series we take a look at the cheese and dairy industry across the United States. Each month we examine a different state or region, looking at key facts and evaluating areas of growth, challenges and recent innovations. This month we are pleased to introduce our latest state — Idaho.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — Potatoes may be the agricultural crop people commonly associate with Idaho, but an influx of new cheese plants and plant expansions, together with strong growth in milk production, have in recent decades helped propel Idaho to one of the top-producing dairy states in the country.

Idaho’s Magic Valley in the south central area of the state is home to 14 dairy processing plants including three Glanbia Foods locations in Richfield, Gooding and Twin Falls; Davisco-owned Jerome Cheese and a Darigold plant in Jerome; and Gossner Foods in Heyburn. Eastern Idaho has three plants and the western Treasure Valley has five dairy processors, including Sorrento Lactalis in Nampa, MeadowGold in Boise and two more Darigold plants in Boise and Caldwell.

|

| COW CONCENTRATION — Idaho’s Magic Valley in the south central part of the state is home to 375,548 or 72 percent of the state’s dairy cow population. Fourteen of Idaho’s 22 dairy processing facilities also are located in the Magic Valley region. |

Jerome cheese, which kind of set the tone for more growth,” says University of Idaho Extension Economist Wilson Gray of Davisco’s Jerome facility, which was built in 1991 and expanded in 1997 to include a new 67,000-square-foot whey processing facility.

“Then Glanbia also expanded quite a bit along with other processors in the state,” Gray says. “They had the ability to take the milk without it having been transported too far. It was in good proximity to some of the West Coast markets.”

Currently Idaho is the second-largest milk producer of the 12 western states and fourth in the entire United States. With on-farm cash receipts from milk totaling $2.1 billion last year, dairy now is Idaho’s largest agricultural industry.

“The dairy industry surpassed potatoes many years ago in sales receipts,” says Cheri Storey, communications director, United Dairymen of Idaho.

• Valley of cows

Dairy processors have concentrated in Idaho’s Magic Valley to be close to the state’s milk supply, which is most abundant in this region. Approximately 72 percent of the state’s half million dairy cows are located in this part of the state, which attracts farms with its milder climate, heavily agricultural areas and proximity to processing facilities.

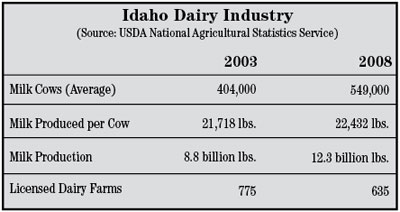

While farm numbers in Idaho have declined like in most other states, cow numbers and production has continued to increase year-to-year. According to USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), milk production in Idaho has more than doubled in the last decade, from 5.8 billion pounds in 1998 to 12.3 billion pounds in 2008.

“The growth historically has been due to favorable climate and feed, particularly on the roughage side,” Gray says.

All but one of Idaho’s dairies are family-owned, and they range from 50 cows to 15,000 cows. Of the 635 licensed dairy farms in 2008, Gray says about 500 of them have less than 1,000 cows, while the large dairies (1,000 cows or more) own about 70 percent of the cows.

“We still have quite a few small farms,” Storey says. “I think that’s one of the misperceptions about Idaho, the big dairies. It’s not true, we have a mix — mid-size up to larger farms of 2,000 cows plus.”

• Independent dairy farmers

The Idaho Dairymen’s Association (IDA), which operates under the checkoff-funded United Dairymen of Idaho, was formed in 1944 and represents all the state’s dairy farmers on issues from the political arena to environmental studies to pricing and economic conditions.

IDA Executive Director Bob Naerebout says IDA has been in contact with elected officials’ offices to assert the organization’s positions on supply management and support prices.

“IDA has a very strong free-market mentality,” Naerebout says, adding that during a recent board meeting, members reaffirmed their opposition to price support programs and increasing price support levels.

“They’re quite a progressive group of dairymen that recognize that government programs do not necessarily benefit them or the dairy industry as a whole,” Naerebout says.

Idaho was part of the federal milk marketing order system until 2004, when there was a move to make modifications to that order and the state’s dairy producers voted it out in April of that year.

“Idaho dairy producers are very independent. They don’t want the government in their business,” Storey says.

The impact of not being part of a federal order has been minimal, Gray says. While some processors were able to benefit from pooling, others had been hurt by negative price differentials, and there hasn’t been any move since to put in another order.

“In general, I don’t think most producers are unhappy with it being gone,” Gray says.

• State of cheese

Cheese production in Idaho has increased from 515.0 million pounds in 1998 to 805.3 million pounds in 2008, according to NASS, and Idaho is the third-largest manufacturer of natural and processed cheese in the United States. Approximately 93-95 percent of the state’s milk production volume goes toward cheese manufacturing.

“We’ve always been pretty high in terms of the percentage going into processing,” Gray says. “We produce a lot of milk, and there is not a fluid market close by. Cheese traditionally has been our main product.”

Cheese companies continue to look to Idaho as a place to expand. In October 2005, Utah-based Gossner Foods held the grand opening of its Heyburn cheese facility located in Idaho’s Magic Valley. The facility was built to help meet a growing demand for the company’s Swiss, and it now also manufactures Muenster and minihorns in Colby, Colby Jack and Pepper Jack varieties.

The plant, which employs about 50 people, processes approximately 759,000 pounds of milk a day and has the capacity to process 1 million pounds a day. Company officials say the Magic Valley plant is where they see growth continuing in its Swiss and other cheese varieties.

“There was an abundance of milk in that area and a good work force, and the city was very anxious to have us there,” says Delores Wheeler, president and CEO, Gossner Foods. “We are very much pleased. It’s worked out very well for us.”

Wheeler says about 20 producers from the Magic Valley area supply the plant with milk, and there is room for the plant to grow as needed.

“We have excellent dairy producers up there that provide us with very high-quality milk,” Wheeler says. “It’s been an excellent decision of ours to go there, and we’ve been very happy with the surrounding area, farmers and employees. The community has been great to work with.”

Glanbia Foods Inc., based in Twin Falls, Idaho, has been in the state since the early 1990s (it changed its name from Avonmore West to Glanbia Foods in 2000). Glanbia is the largest milk buyer in the state, says Russ De Kruyf, director of milk procurement, Glanbia Foods, and president of the Idaho Milk Processors Association (IMPA).

“It’s a great place to have a plant. That’s why we’re here, and that’s why others have built here,” De Kruyf says.

• Present struggles, future growth

In the last year, two new milk powder processors — Idaho Milk Products and High Desert Milk — have opened in Idaho, increasing the state’s production capacity by about 5 million pounds of milk per day, De Kruyf says. However, he adds that growth of the Idaho dairy industry as a whole is unpredictable as it waits for the economy to rebound.

“We obviously are watching the current financial crisis for dairymen very closely,” he says. “There is a lot of financial stress on the dairy farm. There are some new permits some dairymen are sitting on to build. They are not building now and are more in survival than expansion mode.”

In addition to dairy processors and producers, De Kruyf says owners of businesses such as car and furniture dealerships in the state have been affected by recent economic struggles in the dairy industry.

“People I know ask how the milk prices are, as their businesses are very related to the dairy industry,” he says. “People are getting it now, how reliant the state of Idaho is on the dairy industry.”

Naerebout says Idaho’s dairy producers currently are in as bad if not a worse position than most dairy farmers in the United States. Milk prices recently have averaged below $9.70 per hundredweight, falling to averages between $5-$6 per hundredweight below their costs of production.

“Idaho’s dairy producers are almost the lowest-paid in the country for milk price,” Storey says, adding that Idaho also has been in drought for many years.

“We try to do things to reduce water consumption,” she says “While the climate is pretty mild, Idaho has had water issues for years.”

De Kruyf says while water supply is one of the limiting factors in Idaho’s dairy industry, luckily the state does have a replenishable supply. However, Idaho is not exempt from some water wars with other industries such as trout raisers and other ground and surface users.

Despite recent challenges, Gray says Idaho hasn’t seen the loss of many farms yet. Dairy farmers have been doing quite a bit of culling, and he says some have taken advantage of the Cooperatives Working Together buyout rounds.

“We’ve seen some reduction in cow numbers because of economics over the last several months, and we will see more of that over the next year because of the economic situation,” Gray says. “Longer-term, I think the industry will probably grow a little more and stabilize a little more.”

He adds that in the next 3-5 years, the industry might grow from 550,000 cows to stabilize around 600,000 cows.

Naerebout says while a few years ago the state was short of processing capacity, currently the balance of producers and processors is relatively even.

“About three years ago, I would have said there was plenty of room for more processors,” he says. “Right now we have lost production about a percent and a half. With two new plants opening up, we are at a comfortable capacity.”

Storey says while it may be too early to tell when the Idaho dairy industry will stabilize and start to grow again, United Dairymen of Idaho is doing everything it can to help move product.

“The Idaho dairy farmers work very hard. I hope consumers value the product they produce,” Storey says. “As one of the largest dairy-producing states in the country, I hope they have the ability to continue on their farms, producing wholesome food.”

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090