|

|||

|  |

|

|

Demand for New Zealand’s pasture-based dairy grows

Editor’s note: Passport to Cheese is Cheese Market News’ feature series exploring the dairy industries of nations around the world. Each month this series takes an in-depth look at various nations/regions’ dairy

industries with coverage of their milk and cheese production statistics and key issues affecting them. The nations’ interplay with the United States, including both imports and exports, also will be explored. This month we are pleased to introduce our latest nation — New Zealand.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — New Zealand is a small country with a big dairy presence, both domestically and around the world. The island nation of just more than 4.6 million people is now home to 5.0 million milk cows and 11,970 dairy farmers, according to the latest dairy statistics released earlier this month by the industry-funded organization DairyNZ.

The lush country is well-known for its pasture-based dairies. The average New Zealand cow lives in a herd of 419 cows, and 74 percent of dairy herds are located in the North Island, with the greatest concentration in the Waikato region, according to DairyNZ. Milk production peaks in October, which is spring in New Zealand.

“It’s also when pasture is at its most plentiful and highest quality on farm, providing a perfect synergy which helps to make New Zealand’s pasture-based farming system so efficient,” says Greg Hamill, genetics business manager of New Zealand-based Livestock Improvement Corp. Ltd. (LIC). “That’s our core competitive advantage here in New Zealand — a cost-efficient pasture-based farming system, using great cows that are fed well.”

• Cheese industry

The pastures of New Zealand come through in its cheeses as well. The country boasts around 300 different types of cheeses made by 40 cheesemakers, according to Corrie den Haring, general manager at Green Valley Dairies in Auckland, New Zealand, and board member of the New Zealand Specialist Cheesemakers Association (NZSCA).

“One of the unique factors of New Zealand cheese is its clean freshness,” den Haring says. “This is partly derived from having grass-fed animals, which imparts a clean profile not often seen in other countries’ products.”

As a former British colony, New Zealand’s cheeses were strongly influenced by the British and traditionally it made Cheddar to export back to England. New Zealand’s specialty cheese industry began in the 1950s when some Blue-vein styles emerged. After World War II when a number of new immigrants arrived in the country, cheese styles began to diversify.

“After the introduction of Blue vein in the 1950s, other variations of ‘yellow hard cheese’ also started, with Colby and variations of the British-style cheeses,” den Haring says. “Then in the late 1970s, numerous Dutch cheesemakers began starting up and Gouda/Edam style cheeses took off mainly for the immigrant Dutch community. In the 1980s a number of more adventurous businesses started with French-style cheeses, Camembert and Brie. Also at that time the Blue-vein types also expanded away from the acid/Danish-style to more rounded softer French-style products.”

Lately New Zealand has seen a number of Italian cheesemakers introducing Mozzarella, Provolone and a range of semi-soft cheeses, den Haring says. Popular cheeses in the country still include Camembert, Blue and Gouda/Edam styles, while Italian and flavored cheeses are fashionable, den Haring adds.

Of the 40 cheesemakers in New Zealand, seven make non-cows’ milk products (goat, sheep or buffalo). Three are “large” specialized cheese companies that process more than 10,000 liters of milk a day, while most process 500-5,000 liters a day.

“We are a country of two industries,” den Haring says. “The large multinationals making milk powder, butter, Cheddar cheese, etc., and small independent cheesemakers selling domestically.”

Some medium-sized producers also export cheese, he says, but the vast majority of independent cheesemakers sell locally due to the high costs, compliance standards and distances involved in exporting.

• Fonterra

In 2001, New Zealand’s two largest dairy cooperatives merged to form Fonterra Cooperative Group Ltd., which now represents the majority of New Zealand’s milk and is the world’s largest dairy exporter. Key markets for Fonterra include New Zealand, Australia, Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, China, Chile and Brazil.

New Zealand’s Dairy Industry Restructuring Act of 2001 (DIRA), which authorized the creation of Fonterra, also was designed to temper Fonterra’s market dominance in the country’s dairy industry.

DIRA regulations require Fonterra to supply independent dairy processors with up to 50 million liters of raw milk per independent processor, capped at a total of 795 million liters per season of the raw milk it collects. According to the New Zealand Commerce Commission, this provides a stepping stone for new processors and an ongoing source of supply for niche producers. DIRA also promotes the setting of a base milk price that provides an incentive for Fonterra to operate efficiently while providing for contestibility in the market for the purchase of raw milk from farmers.

This has made things both easier and harder for New Zealand’s independent cheesemakers, most of whom obtain their milk from local farmers or from Fonterra, den Haring says.

“Easier because Fonterra is obliged to sell milk at the farmgate price — they technically make no money from selling this milk — so price is reasonably predictable and competitive, however, you have no control over what farm or what milk you get,” he says.

The “rules” for getting this milk also are somewhat restrictive, he adds, as there is a minimum delivery of 3,000 liters plus transport charges from Fonterra that make buying smaller quantities non-viable.

“So for a small cheesemaker taking, say, 1,000 liters a day, this does not work,” he says. “There is little ability to buy milk from other dairy companies as there is no reason for them to sell.”

Some have been critical of Fonterra’s ability to create optimal returns for New Zealand’s farmers, but Fonterra maintains that it has been successful over the last 14 years and remains largely supported by the country’s dairy industry.

In a response to a recent critical New Zealand Herald article, Fonterra Chairman John Wilson noted the cooperative’s “unique strength coming from being a vertically-integrated supply chain with scale, connecting high-quality milk from pasture-raised cows to consumers around the world.”

He highlighted growth of Fonterra’s milk powder, consumer and foodservice revenue over the last decade, and noted that in the past two years, an unprecedented NZ$230 million has been invested in consumer and foodservice processing capacity in New Zealand to supply export products to Asian markets.

In May, Fonterra doubled its Mozzarella production at its site in Clandeboye, New Zealand, where it now makes enough to top more than 300 million pizzas a year in foodservice export markets in China, Asia and the Middle East. And earlier this month, Fonterra opened a new production line that doubles its sliced cheese capacity at its Eltham, New Zealand, plant.

“Once completed, we’ll be able to make around 2.3 billion slices of cheese each year out of Eltham, all of it sold into growth markets in Australasia, Asia and the Middle East,” says Mark Leslie, Fonterra director of New Zealand manufacturing.

Foodservice is a fast-growing market for Fonterra, with more than NZ$150 billion of dairy products purchased by this sector every year. Fonterra is the largest supplier of shredded Mozzarella and slice-on-slice processed cheese to global QSR (quick-service restaurant) brands in the Asia Pacific region.

During the China Business Summit held in Auckland earlier this month, Fonterra CEO Theo Spierings highlighted the growth of the company’s ingredients and foodservice businesses in China over the last five years.

“Our ingredient business grew from a NZ$1 billion to a NZ$4 billion business (through 2014),” Spierings says.

“Foodservice we grew in China from a NZ$600 million business in that time period to a NZ$1.5 billion business, and we’re going very quickly to NZ$2 billion. To put that in context, that’s like the entire wine business in New Zealand.”

• Exports, global competition

New Zealand’s main dairy commodity is whole milk powder (WMP), and it sells much of this to the Chinese market. However, as China’s demand for WMP imports has plummeted this year, New Zealand has made up with more exports of cheese and other commodities, says Al Levitt, vice president of communications and market analysis, U.S. Dairy Export Council (USDEC). He adds that New Zealand’s recent increase in cheese exports has resulted in more competition with the United States, particularly in foodservice markets in Asia and the Middle East.

Fonterra notes in its annual financial results that it has adjusted its product mix away from WMP toward products such as cheese and casein, taking advantage of better pricing opportunities in Japan and the United States.

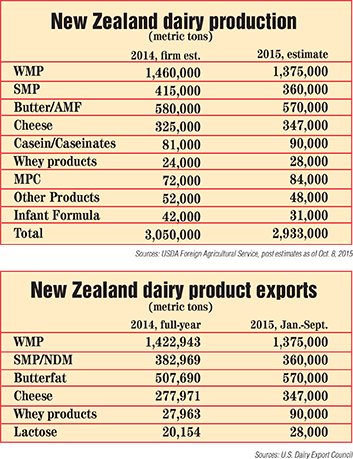

New Zealand is expected to produce 1.38 million metric tons of WMP in 2015, 6 percent below the 2014 total, according to the New Zealand Annual Dairy and Milk Supply Report 2015, released last month by USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service. WMP exports by New Zealand are estimated to drop 4.4 percent to 1.36 million metric tons in both 2015 and 2016.

Meanwhile, USDA says New Zealand cheese production in 2015 is estimated to total 347,000 metric tons, up 7 percent from 2014, and total cheese exports for 2015 are forecast at 316,000 metric tons.

“This situation is likely to reverse in 2016 as the price relativity between WMP and cheese starts to favor WMP again,” the USDA report notes.

In 2016, New Zealand cheese production is forecast at 310,000 metric tons and exports will fall back to 2014 levels at 278,000 metric tons, the report says.

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090