|

|||

|  |

|

|

France promotes tradition of cheesemaking excellence

Editor’s note: Passport to Cheese is Cheese Market News’ feature series exploring the dairy industries of nations around the world. Each month this series takes an in-depth look at various nations/regions’ dairy industries with coverage of their milk and cheese production statistics and key issues affecting them. The nations’ interplay with the United States also is be explored. This month we are pleased to introduce our latest nation — France.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — It can be difficult to have a conversation about cheese without bringing up France, or visa versa, as cheese is such a central part of French cuisine, and French cheese a centerpiece of fine cheese shops around the world.

“When you say ‘France,’ you think cheese, cuisine. They are known for taking time for living life and enjoying living. When they make something, they really get into the process,” says Colette Hatch, a cheese, food and wine consultant based in Santa Rosa, California.

Hatch, a French native with a background in restaurant and hotel management, says when she moved to Sonoma County 20 years ago, Americans — and even prominent chefs — were not very familiar with French cheeses.

“When I started 20 years ago, Camembert was not known at all. French cheeses were not well known,” she says.

“Cheeses was not a subject chefs understood well.”

She started to bring goat cheeses, Époisses, Comté and other cheeses over from France and gave classes on French cheeses. At the same time, she says, French cheeses began to gain popularity on the East Coast and in larger cities across the United States.

• Cheese export markets

As interest in French cheese began to grow in the United States, French cheese producers saw their domestic market stagnate and began looking for new markets.

One of the first French cheese companies to start exporting its products is what is now Isigny Ste. Mére, a 500-farm cooperative, following the merger of the Isigny-sur-Mer and Sainte-Mére cooperatives in 1980. Among the cooperative’s specialties are PDO Normandy Camembert, PDO Pont l’Evéque, Mature and Extra Mature Label Rogue Mimolettes, and butter.

“Isigny has a long story of exports,” says Benoit de Vitton, manager for the Americas, Isigny Ste. Mére. “The visionary heads of the co-op understood the French market was going to be matured and saturated at some point, and they had to find growth outside of France.”

The market for French cheeses in the United States started at the end of the 1970s, and de Vitton says it became a more long-term, committed market at the end of the 1990s when the trend and interest for cheese increased.

The cooperative established its first U.S.-based offices in 2001. Today, 56 percent of Isigny Ste. Mére’s production is exported, and the United States is one of its main markets for cheese.

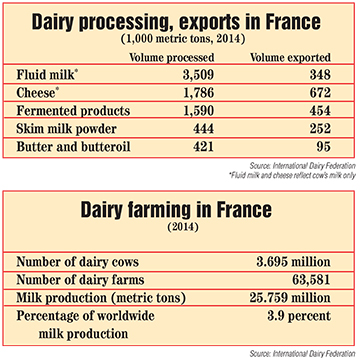

In 2014, France produced 1.8 million metric tons of cow’s milk cheese, 94,780 metric tons of goat’s milk cheese, 33,890 metric tons of sheep’s milk cheese and 30,700 metric tons of mixed milk cheese, according to the International Dairy Federation’s (IDF) World Dairy Situation 2015 report. France’s cheese exports in 2014 totaled 672,000 metric tons.

“Twenty to 30 percent of the cheese is exported. It’s a big part,” says Diane Sauvage, USA branch manager of Interval Export, which exports specialty cheeses and butters from 14 companies in France. “It’s the only way to grow. In France the market is pretty flat, so export is very important for them.”

Russia used to be a very large market for French cheese, but it is now closed to European cheeses due to counter-sanctions imposed in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Sauvage notes that Australia, Japan and the Middle East are among the fastest growing markets for French cheese and butter.

Rachel Perez, who offers sales support and marketing for six French cheesemakers in the United States through The French Cheese Club, says the United States is the biggest market for French cheeses, but the rest of the world collectively is bigger.

“Asia right now is really trending,” Perez says. “Upper-middle class Chinese people are starting to drink wine, which is a status symbol. Now they’re adding cheese onto that also.”

North America also has new opportunities, she adds, as the traditionally protectionist Canadian market is set to lift quotas on many French imports, and U.S. consumers continue to seek specialty cheeses.

“The sheer number of cheese consumers in the U.S., and outlets like Costco, Trader Joe’s Whole Foods and Wegmans, are an indication that the U.S. market will continue to grow and develop,” she says.

• Make it Magnifique

French cheese exports to the United States have had much success over the past decade due in large part to the efforts of The Cheeses of Europe, a marketing program for exports funded partly by French dairy farmers and partly by the European Union. The Cheeses of Europe’s most recent campaign is called “Make it Magnifique.”

“By adding French cheese, it makes a dish ‘magnifique,’” says Wassila Satouri, senior account executive for Fifteen Degrees, the agency handling the 3-year campaign. “Even something as simple as mac and cheese, if you change it to French cheese, like Mimolette, it makes it amazing.”

In addition to its website, thecheesesofeurope.com, which includes videos, recipes and other information about French cheeses, there are a Cheeses of Europe pairing app, TV, print and online advertising, 1,000 in-store demonstrations a year, and several pop-up and press events promoting French cheeses.

The main goal of the campaign is to educate consumers about French cheeses. Last month, the campaign hosted an event that featured bloomy rind French cheeses such as Brie, Camembert and triple creams.

“We explained a Brie is not always the same Brie. It depends on the process, what grass the cow ate, what farm the milk was produced. They see the difference in color and taste,” Satouri says.

“For some of the cheeses we present, it’s from a very small herd, like 40 cows,” she adds. “Also we keep the tradition to produce cheeses for 100 or 200 years — we keep the same process.”

Satouri says studies done after promotions to measure their effect have shown an increased knowledge and awareness of French cheeses.

Sauvage says Interval Export has definitely seen increased U.S. interest in French Cheeses in the past 10 years since the Cheeses of Europe program started in the United States.

“This helped a lot in order to go to the U.S.,” she says. “They offer a lot of demos. This is key when a cheese is new on the market. They also offer marketing support, really promoting French cheeses, why they are good, and why people should use them more.”

• Preserving traditions

France is known for its small farms and traditional handcrafted cheeses, many of which hold designations of protected origin (PDO or AOP), meaning they are limited to certain cheesemaking and dairy farming regions and must conform to strict standards and methods of production.

“A lot of preservation has to do with the PDO system,” says Perez, adding that in addition to preserving traditional cheesemaking arts, this system also helps to ensure quality and natural cheeses.

“We’re starting to work with organics, but for the French, ‘organic’ is a nebulous term. They fundamentally are organic,” she says. “I think Americans are looking for quality but want to recognize it with certifications. The French already have quality set up with the PDO system. Investing into that extra certification, to them, is kind of a foreign concept.”

Isigny Ste. Mére is famous for its AOP products, de Vitton says, and various aspects of the Normandy region give its products their defining attributes.

“Why such great products? Because of the terroir,” de Vitton says. “The climate is very mild, almost all year round. There is grass that grows very green and very well. About three months of the year, a big part of the field is covered with water, and the salty taste comes from the sea. Norman cows, the breed most present in Normandy, produce the highest fat content and protein content in France.”

He also says the preservation of France’s dairy farming and cheesemaking traditions are very much linked to the AOP or PDO system, which dictates the feeding of the cows and the size of land that the cows need to have. The average farm size in the cooperative, he says, is 45 cows.

“If you have 30 cows, you need 30 hectares. If you have 30 hectares, you are not allowed more than 30 cows,” he says. “Farming in France and Normandy has nothing to do with thousands of cows. It’s very traditional farming. People love the animals and take care of them. They have been doing this for generations. It’s still very traditional.”

• Changes and challenges

Its dairy farms may be small, but France is home to some of the world’s largest dairy processors, including two of the top 3 (Danone and Lactalis), and two more of the top 20 global dairy companies (Sodiaal and Savencia, formerly Bongrain), according to Rabobank. A Euromonitor report notes that Groupe Lactalis led the nation in cheese sales in 2015 with a 21 percent value share of the French market.

French people consumed a total of 1.7 million metric tons of cheese or 26.7 kilograms (58.9 pounds) per capita in 2014, according to IDF’s World Dairy Situation report. While cheese remains a major staple in their diet, the types of cheese French consumers prefer is changing.

“In 2015, the main growth drivers in cheese were products positioned as meal solutions or for snacking,”

Euromonitor reports. “Such products include ingredients for salads, savory pies and other recipes such as Mozzarella, Feta and other cheese cubes, slices of Raclette (included in packaged hard cheese) and recipes for fondue, traditional culinary cheese (grated cheese, sticks, slices for sandwiches) and cheese for apertifs and tapas. Such products continued to gain ground at the expense of basic platter cheese that is usually consumed at the end of a meal, including for instance Camembert and Coulommiers, Blue veined cheese and even goat cheese — although the main reason behind the slow performance of the latter was a shortage due to the bankruptcy of some dairies in 2014.”

Another change is a decline in the number of small, traditional cheesemakers. Perez notes a steep decline since 2000 in the number of raw milk Camembert producers.

“There’s a very romantic idea in the U.S. of going back to farms and herds. Especially with millennials, it’s very trendy,” she says. “In France, it’s very opposite. Everyone is looking to get out of the country and into the city.”

Additional challenges for small cheesemakers in France include export regulations, particularly following the passage of the U.S. Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA).

“Since the passage of FSMA, there is a lot more paperwork and bureaucracy. HACCP plans, third-party audits, at least at the beginning of this process are complicated. Getting their ducks in a row for FSMA definitely is a challenge,” Perez says.

She adds that some of the smaller and more specialty artisan producers in Europe are no longer exporting to the United States because of these challenges.

“In reality, I think there will be less imports, and what we will see is going to be very industrial,” she says. “I see when I go to cheese shows in France, people used to be interested in the U.S. market. Now if you say you’re from the U.S., some don’t want to bother with you anymore.”

Hatch says when she returns to visit family in France, she looks to fill the refrigerator with a variety of cheeses. However, in the last few years, she noticed a smaller variety of specialty cheeses available.

“As the EU added regulations, there were shifts in making cheese. Some small producers could not follow or be bothered by their application and began to let go,” she says. “I couldn’t find too many good raw milk cheeses. It was horrible!”

This last year, though, she says she was able to find more of these cheeses.

“They were definitely made again with more care and more love. They are coming back.”

Hatch says she believes recent focus on slow foods and television shows about food production may have helped to renew interest in traditional French raw milk cheeses.

“I think the French always assumed their food was delicious and would be good,” she says. “So they assumed it was continuing the same way, until programs started to be aired on TV. They realized, ‘We’re not eating the good stuff anymore. Something is wrong.’ I think that’s what really helped to bring back the awareness.”

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090