|

|||

|  |

|

|

Canada grows cheese sector to meet global trade demands

Editor’s note: Passport to Cheese is Cheese Market News’ feature series exploring the dairy industries of nations around the world. Each month this series takes an in-depth look at various nations/regions’ dairy industries with coverage of their milk and cheese statistics and key issues affecting them. The nations’ interplay with the United States also is explored. This month we are pleased to introduce our latest country — Canada.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — Across the northern U.S. border, Canada’s cheese industry reflects some similarities to the U.S. industry. As in the United States, commodity cheeses like Cheddar and Mozzarella traditionally have dominated Canada’s market, though artisan and farmstead cheeses have emerged in the last couple decades to find growth alongside local food movements and interest in high-end cuisine.

|

Photo courtesy of The Great Canadian Cheese Festival |

TASTE OF CANADA — Margaret Peters-Morris (left), owner and cheesemaker at Glengarry Fine Cheese, Lancaster, Ontario, gives samples to attendees of The Great Canadian Cheese Festival, an event held every summer in Picton, Ontario, showcasing artisan producers from across the country. |

Canada’s dairy industry, however, is quite different in other aspects. It serves a much smaller population, runs under a supply-management system and is more focused on fulfilling domestic demand, with relatively low export activity.

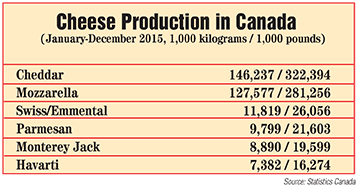

In 2015, Canada produced a total of 438.4 million kilograms (966.5 million pounds) of cheese, more than half of which was Cheddar and Mozzarella, according to data from the Canadian Dairy Information Centre, maintained by the dairy section of the government’s agriculture department. The vast majority of this cheese is produced in Quebec and Ontario. Canada’s largest dairy processors are Quebec-based Saputo and Agropur, and Parmalat Canada of Ontario. More than 1,000 varieties of cheese are produced across Canada.

• Promoting local cheese

“In Canada’s total cheese market, Cheddar and Mozzarella still dominate and probably will for many years to come,” says Georgs Kolesnikovs, founder and director of The Great Canadian Cheese Festival. “In artisan cheeses, we now — as in the U.S. — have such a huge variety being produced from fresh to Blue to aged, clothbound Cheddars to flavored cheeses, which have become very big over the last couple of years.”

As the local food movement started to catch fire over the last decade, Kolesnikovs says, he noticed more and more Canadian artisan cheeses entering the market. Inspired by U.S. cheese festivals and other food and wine events, in 2011 he launched the first Great Canadian Cheese Festival in Picton, Ontario. Featuring exclusively Canadian artisan cheesemakers as well as other artisan food producers, small-batch wineries and craft breweries, the festival has grown in popularity every year, last year exceeding 5,000 attendees. This year’s Great Canadian Cheese Festival will be held June 4-5 and feature about 150 different cheeses.

To help further promote Canada’s artisan cheese industry, Kolesnikovs also launched the biennial Canadian Cheese Awards in 2014, the first major contest in the nation to include cheeses made with all types of milk. This year 64 producers submitted 301 cheeses for judging. Winners will be announced April 14.

The other major cheese competition in Canada is the biennial Canadian Cheese Grand Prix, launched in 1998 and sponsored by Dairy Farmers of Canada (DFC), an industry-funded organization that conducts a number of marketing, nutrition, policy and lobbying initiatives. The Grand Prix features cheeses made from 100-percent Canadian cow’s milk.

Cheesemaker and dairy farmer Debra Amrein-Boyes, owner of The Farm House Natural Cheeses in the Fraser Valley of British Columbia, won the 2015 Grand Prix championship in the Firm Cheese category for Heidi, a Gruyere-style cheese. She says contests like the Canadian Cheese Awards and Canadian Cheese Grand Prix, along with DFC’s other marketing efforts, help to bring awareness to her family-run farmstead cheese business.

“DFC has a huge budget and does a lot of marketing,” Amrein-Boyes says. “They present cheeses on food shows and to chefs. It’s good for marketing and increased sales.”

DFC uses a number of different vehicles to promote Canadian cheese and dairy products, including contests, advertising, partnerships, educational programs and media relations, says Sandra Da Silva, DFC assistant director, external communications.

“From our popular Milk Calendar, our prestigious Canadian Cheese Grand Prix and our All You Need Is Cheese programs and promotions, to high-profile television and print advertising campaigns and creative in-store programs, we work hard to convey messages about Canadian dairy products and their outstanding value, variety and quality that can easily be part of a healthy diet,” Da Silva says.

• Quotas and regulations

As Canada’s milk and dairy production is managed mainly to meet domestic requirements, the country’s dairy sector operates under a supply management system based on planned domestic production, administered pricing and dairy product import controls.

Amrein-Boyes says there are pros and cons to this system.

“We purchase quota and the supply is managed so the customer always has a supply of milk in the store. There is never a surplus. Farmers are not required to find their own contracts,” she says.

However, the expense of purchasing additional quota can make dairy farm expansion a lofty investment, which is one reason Amrein-Boyes and her family decided to diversify into cheesemaking. The farm switched from Holstein cows to a small herd of Guernsey and Brown Swiss cows and started processing cheese in 2004. The farm recently became certified organic and also is adding a non-GMO verification.

Canada has two different levels of licensing and inspection for dairy processors — federal and provincial.

Businesses that are only provincially-licensed, like The Farm House Natural Cheeses, are not allowed to sell their products wholesale outside of their province. In 2014, Canada had 273 federally-registered dairy establishments and 171 that were provincially-licensed only. Some provinces also have plant quotas, limiting the types of cheeses that can be made in a given facility.

• International trade

Canada is not a large exporter of dairy products. However, major Canadian dairy exports include cheese, whey products, skim milk powder, yogurt, whole milk powder and milk protein concentrates, according to the Canadian Dairy Information Centre. In 2015, Canada exported a total of 8.4 million kilograms (18.4 million pounds) of cheese worth C$55.5 million. Major markets for Canadian dairy exports include the United States, Egypt, the Philippines and Cuba.

With its supply management system and high import tariffs, Canada’s dairy market can be a challenge for trading partners. In 2014, Canada imported C$900.1 million worth of dairy products — mainly cheese, milk protein isolate, whey products and casein from the United States, New Zealand, Italy and France.

“Trade barriers are by far our biggest concern in the Canadian market,” says Shawna Morris, vice president of trade policy, U.S. Dairy Export Council. “Access is constrained with 200-300 percent tariffs. The demand certainly is there in Canada, but tariffs keep exports in check within the confines of what is permitted under their laws.”

However, as trade deals with the European Union (Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement or CETA) and Pacific Rim countries (Trans-Pacific Partnership or TPP) are concluding, the United States and other countries will have some additional access to the market — and Canada’s dairy industry is bracing for new foreign competition.

“Currently, the issues that are of most concern to Canada’s dairy farmers and the industry are the impacts of both CETA and TPP,” Da Silva says, adding that CETA is expected to be signed this year and take effect in 2017. “We have been in constant contact with the government, and we trust they understand that compensation needs to be confirmed before Canadian dairy farmers begin to experience losses due to the 17,000 (metric tons) of cheese that will come into the Canadian market from the EU as a result of this deal. When both the CETA and TPP trade deals come into full effect, there are expected losses in the millions for dairy farmers and the industry as a whole.”

Amrein-Boyes says this anticipated new influx of foreign cheese has caused “a bit of a storm” in Canada’s cheese industry and will make it even more important for local cheesemakers to develop strong relationships with customers.

“For local cheesemakers, it is part of our mandate to educate the public and build relationships with our clients so we can introduce them to new, innovative flavors,” she says. “In a global marketplace and competing against cheaper imports, it’s important to develop good relationships locally. Then we will have a good opportunity to grow our business.”

• New opportunities

Some Canadian cheesemakers also are viewing developments in global trade as new opportunities. Margaret Peters-Morris, owner and cheesemaker at Glengarry Fine Cheese in Lancaster, Ontario, is expanding cheese production this year and looking to enter foreign markets in 2017, starting with the United States.

Glengarry’s Celtic Blue Reserve was named Best of Show at the 2015 American Cheese Society competition and its aged Lankaaster won Supreme Global Champion at the 2013 Global Cheese Awards in England, giving the company international attention and the opportunity to market its cheeses across the Canadian border.

Peters-Morris hopes this expansion will help pave the way for export opportunities for other Canadian artisan cheesemakers.

“We have to start somewhere. We have had a lot of attention internationally, so we are taking the first step for the rest of the processors,” Peters-Morris says. “We have been closed off to exports for many years due to politics. It’s time for Canada to look at that more seriously.”

She says cheesemakers are allowed to export, but due to the country’s rigid pricing structure under supply management, it has been difficult to compete in international markets.

“Our government is looking at ways to allow our processors to play in that export field,” she says.

“The timing is here now. Currency is in a good position for export. We can be competitive in some sectors, like specialty cheese and higher-end quality cheese. Canada does have some really exceptional products.”

Glengarry Fine Cheese already has been served in high-profile international venues such as the Toronto Film Festival and shipped to Buckingham Palace. In addition to the United States, the company plans to enter markets in the Netherlands, France and Saudi Arabia.

“We have to drive that momentum on our name and let everyone else follow. We want everyone else to benefit from this too,” Peters-Morris says, adding that she believes Canada’s artisan cheese industry will continue to be dynamic. “It’s not a huge country, but I really feel this sector is going to be important to us. I think it’s going to have a big impact — I would like to see that for Canada.”

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090