|

|||

|  |

|

|

Australia looks to multiple markets for dairy profitability

Editor’s note: Passport to Cheese is Cheese Market News’ feature series exploring the dairy industries of nations around the world. Each month this series takes an in-depth look at various nations/regions’ dairy industries with coverage of their milk and cheese statistics and key issues affecting them. The nations’ interplay with the United States also is explored. We are pleased to introduce our latest country — Australia.

By Rena Archwamety

MADISON, Wis. — Australia, a continent known for its varied expanses of land, has a longstanding reputation for its variety of quality dairy products and exports.

“Australia has a reputation of a clean and green environment where our cows roam freely in the paddocks,” says Alex Evans, media relations manager for Devondale Murray Goulburn, Australia’s largest dairy foods company and exporter.

|

“Our customers appreciate the high quality of dairy products that we make,” Evans adds. “Our products are highly sought after in many markets around the world including China, Southeast Asia and Europe.”

In Australia, the dairy industry ranks third behind the beef and wheat industries based on farmgate production value, according to Dairy Australia, the dairy farmer-supported national services body. Of the country’s 24 million people, approximately 39,000 are directly employed on dairy farms and by dairy companies in Australia.

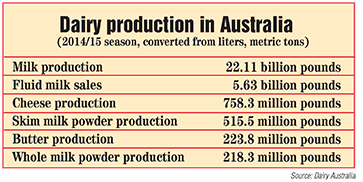

Milk production in 2015 was estimated at 9.73 billion liters (22.11 billion pounds), Dairy Australia reports, and the average herd size currently is an estimated 284 head with a steady trend toward very large farm operations of more than 1,000 cows.

“We have everything from quite small family farms with less than 100 cows to more corporate entities comprised of lots of farms and 3,000-4,000 cows,” says Norman Repacholi, commercial research and analysis manager, Dairy Australia.

“More than two-thirds of milk production is concentrated in the southeast corner, and Victoria is the largest production state. There also has been some fairly reasonable growth in Tasmania,” he says, adding that the southern island state has successfully implemented plans to increase its dairy processing capacity in recent years.

While the southeast is a stronghold for dairy, all states have dairy industries that supply fresh milk to nearby cities and towns, and a range of high-quality consumer products — including fresh milks, custards, yogurts and a wide variety of specialty cheeses — are produced in most Australian states, according to Dairy Australia.

The country’s dairy industry also has drawn investors from around the world, from multi-national dairy giants like Fonterra and Saputo to farmers from Europe and New Zealand looking for more affordable land.

“The Australian dairy industry is very cosmopolitan,” Repacholi notes. “We are very much blended — a lot of international organizations have stake in the industry in addition to Australian owned and operated businesses.”

• Deregulation

In the last few decades, Australia has seen a steady decline both in number of farms and volume of milk produced, Repacholi says. There were around 20,000 dairy farms in the 1980s, but after a fairly long period of consolidation, about 6,100 farms remain.

“There have been a few factors — during that period, the dairy industry was deregulated,” Repacholi explains. “As part of that, farmers were offered a structural adjustment package. They had the opportunity either to take a lump sum of money to grow their farm and make it more competitive, or they had the opportunity to exit the industry.”

A large number of farmers took the opportunity to exit after the government announced in 1999 that it would implement the Dairy Structural Adjustment Program to transition the industry to deregulation. A number of farmers also took the opportunity to buy out other farms and expand their assets to set up a stronger platform, Repacholi says. Australian dairy farmers now operate in a completely deregulated environment where international prices determine the price farmers receive for their milk. Dairy Australia notes that at an average of approximately 42 cents (U.S.) per liter, Australian dairy farmers receive a low price by world standards and therefore have to run very efficient production systems.

“Being an unregulated market, there is no class structure for the milk price,” Repacholi says. “Risk management becomes a larger challenge.”

Processors will announce an opening price at the beginning of the season based on a conservative estimate. Over the year, as processing companies realize what the milk value is, farmers will get step-up payments, paid retrospectively for all the milk produced during that season.

“Unfortunately, one of the challenges recently was a fairly significant step-down situation,” Repacholi says. “Instead of milk companies paying more, they paid a lot less for overall prices that year, which was unexpected for the dairy farmers.”

Now there is discussion on what the most appropriate mechanisms are to balance risk for Australia’s dairy farmers.

“Risk traditionally is transferred back to the farmgate,” he says. “Now there is discussion of, ‘Do we need to establish tools that allow it not just to be transferred, but also mitigated along the value chain?’”

• Processors and cheesemakers

Two major dairy companies — Australia’s Murray Goulburn (MG) and New Zealand-based Fonterra — process about half of Australia’s milk output, Repacholi says.

Evan notes that MG received approximately 3.5 billion liters (8.0 billion pounds) or 36.6 percent of Australia’s milk and generated sales revenue of approximately A$2.8 billion in the 2015/16 fiscal year. MG has approximately 2,200 farmer-suppliers across southeast Australia and 11 processing plants.

MG’s main products include cheese, butter and dairy spreads, milk powders and beverages. Earlier this year, MG entered a five-year national private label contract to supply Coles brand Australian cheese in the domestic market, adding to its 10-year partnership that began in 2014 to supply pasteurized milk for Coles private label brands in Victoria and New South Wales. The company also is building a new cheese processing facility in Cobram, and is planning a new nutritionals plant in Koroit, both in the state of Victoria.

Fonterra also has made recent investments in its Australian cheese production. It is building a new state-of-the-art facility in Stanhope, Victoria, that will produce cheese for Australian consumer, foodservice and export markets. Fonterra Australia also announced last month that it is investing A$4.3 million to boost cheese and whey capacity at its Wynard plant in Tasmania. After the Stanhope and Wynard projects are complete next year, Fonterra says it expects its total Australian cheese production to increase by 50 percent.

Australia produced 344,000 metric tons (758.4 million pounds) of cheese in 2014/15, up 10 percent from the previous year, Dairy Australia reports. Cheddar is the dominant production type, followed by fresh, semi-hard, hard grating and mould cheeses. Dairy Australia adds that there has been a long-term production trend toward non-Cheddar types. The non-Cheddar share of total production volumes has increased from 30 percent three decades ago to between 45 and 50 percent in recent years.

Dairy Australia concentrates its efforts on programs to benefit the country’s dairy farmers, though it also does some post-farmgate research and work promoting health and nutrition benefits of dairy. Since 2012, it also has partnered with the National Centre for Dairy Education to offer webinars for cheesemakers and other dairy manufacturers. The Australian Dairy Products Federation is the primary policy body for commercial and non-farm members of Australia’s dairy industry, focusing on improvements in manufacturing, marketing, trading and distribution. Meanwhile, the Australian Specialist Cheesemakers’ Association (ASCA) operates as a not-for-profit association for Australia’s artisan cheesemakers.

ASCA formed about 25 years ago, modeled after the UK Specialist Cheesemakers’ Association, and its membership is comprised mostly of small-scale farmhouse (farmstead) artisan and specialty cheesemakers. Associate ASCA members come from retail, wholesale and other related sectors.

“Currently, we have approximately 100 members,” says Sonia Cousins, ASCA communications officer, who also is a cheesemonger, cheese education consultant and cheese judge.

“Specialty/artisan cheesemaking in Australia really only began in the early 1980s,” Cousins says. “Since then, it has evolved from extremely niche to reasonably mainstream, with Australian-made specialty/artisan cheeses now available in gourmet food stores, supermarkets and restaurants across Australia.”

An increase in the number of farmers’ markets across Australia has been a significant factor in the increased growth of specialty and artisan cheeses, Cousins notes. This has given small cheesemakers more opportunity to sell and market their products directly to consumers in their local region rather than having to rely on big city distributors.

“This direct relationship between producer and consumer has been beneficial to both, and has allowed cheesemakers to innovate, experiment and push the boundaries with new styles of cheese,” Cousins says.

By far, she says, the most common style of specialty cheeses in Australia are “white mould” cheeses (known as “bloomy rind” in America), especially Brie and Camembert styles.

“Blue cheeses also are quite common, and as a cheese judge I would estimate that white mould and Blue categories are the largest in the major cheese shows,” Cousins says.

“Cheeses made from goat’s milk — and to a lesser extent, sheep and buffalo milks — are becoming increasingly popular as consumers become more adventurous.”

• Dairy exports

On a volume basis, cheese has been Australia’s No. 1 dairy export for some time, Repacholi says.

“A lot of it extends from the export history we have had for decades,” he explains. “Japan is our largest cheese market. A lot of what is produced is targeted ingredient cheese for the Japanese market — pizzas, shred blends and cheese for further processing.”

Although Australia accounts for around 2 percent of the world’s milk production, it ranks fourth in terms of world trade, behind New Zealand, the European Union and the United States, Dairy Australia says. In 2014/15, Australia exported A$820 million worth of cheese, A$683 million worth of skim milk powder and A$365 worth of whole milk powder including infant formula powder. Its major export markets are greater China, Japan and Southeast Asia.

“More recently, we have seen a more targeted approach to exports,” Repacholi says.

“Australia isn’t the lowest-cost producer in the world, so it’s hard to compete just on price. We compete on quality parameters, consistency parameters and co-developing overseas. There has been more engagement. Not all product can be value-added, but that’s where Australian exporters have directed more attention.”

MG, for example, has its own manufacturing (nutritional powder blending), sales and distribution centers in China.

“In other markets, we deal directly with customers or via a network of distributors,” Evans says. “Last year we exported A$1.1 billion worth of dairy products, a combination of ingredients and value-added products. We are currently working on a number of additional partnerships.”

Earlier this year, MG forged agreements with global pediatric nutrition company Mead Johnson Nutrition and Indonesia’s leading nutritional company, Kalbe Nutritionals.

The share of total production exported from Australia has ranged from around 40-60 percent since the late 1990s, though exports have trended on the low end in recent years due to lower milk production, last year hitting about 35 percent.

In addition to the loss of dairy farms after deregulation, adverse weather conditions in Australia also have contributed to a decrease in milk production since the early 2000s, and thus a decrease in dairy exports.

“Shortly after deregulation, we were exporting 60 percent. Unfortunately, the year after was the first of what is termed the ‘millennium droughts,’ which had significant impacts on milk production in Victoria and other parts of the country,” Repacholi says.

Different areas of Australia also have unique production cycles based on climate. In Victoria, farmers can produce twice as much during peak season when more grass is available, posing a challenge for processors to find avenues for the extra milk, Repacholi says. In the more tropical areas of Queensland, production is flatter throughout the year, and therefore more milk from that region goes to the domestic market.

“Probably the biggest challenge is the range of different ways you can solve the problem of producing milk in variable climate environments,” Repacholi says. “One thing Dairy Australia has invested time end effort in is enabling farmers to budget, plan and cope with conditions.”

He adds that processors always are looking at ways to maximize profitability in the domestic market given its relative size, but to unlock demand they see from international consumers.

“I think that’s really the key to what will keep Australian dairy successful in the long run,” Repacholi says. “Multiple strings from multiple markets that will enable growth and profitability.”

CMN

| CMN article search |

|

|

© 2025 Cheese Market News • Quarne Publishing, LLC • Legal Information • Online Privacy Policy • Terms and Conditions

Cheese Market News • Business/Advertising Office: P.O. Box 628254 • Middleton, WI 53562 • 608/831-6002

Cheese Market News • Editorial Office: 5315 Wall Street, Suite 100 • Madison, WI 53718 • 608/288-9090